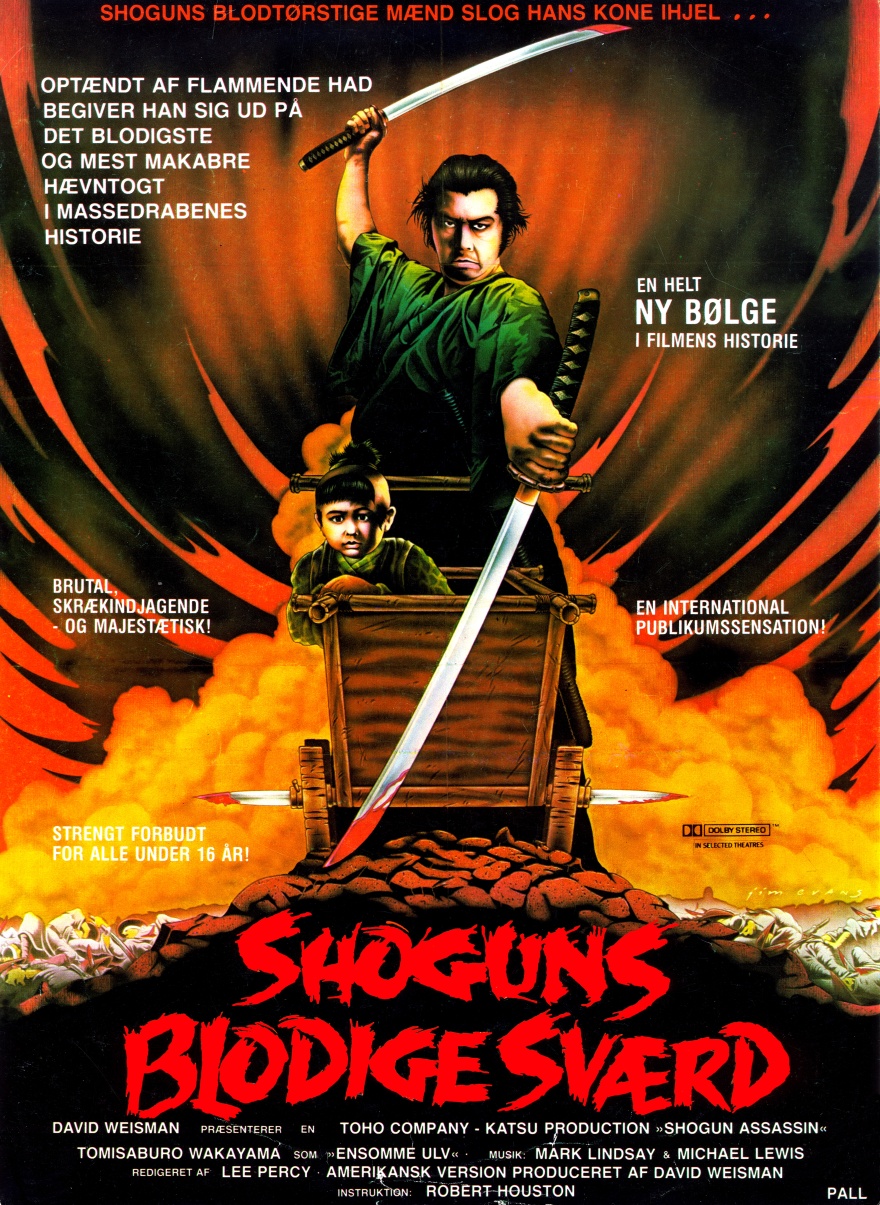

If you watch a lot of films (and I don’t watch as many as I’d like these days, what with having to be a ’grownup’. Well, sort of), it’s easy to become jaded with the whole medium. It’s easy to be struck by the melancholy that’s it’s just not the same as it was when I was a teenager discovering the delights of cinema. Then Film4 shows Shogun Assassin and I fall in love all over again. To many it’s a title that’ll be familiar only as B.B.’s bedtime movie in Kill Bill: Vol. 2, and the influence on Tarantino is immediately apparent. Much of his visual style and thematic fixations seem to be taken directly from Shogun Assassin, and to watch it more fully contextualised Tarantino for me. It’s also totally majestic. I was expecting fun trash, not great cinema. I found both. That it took me by surprise only enhanced things (sorry, now I’m sending you in with the expectations I didn’t have). For a start, it’s not even an original. This is an American dubbed re-edit of not one, but two Japanese films in the Lone Wolf and Cub Series. I very much want to see the originals, and excitingly Criterion are releasing their blu ray boxset of the whole lot – including Shogun Assassin – over here in the UK later in March. It’s hard to imagine the original films being better though. What could be improved? Well alright, the plot could certainly use some work, but then it’s not the kind of film that relies on perfect narrative cohesion. In most cases I’m opposed to english dubbing of foreign language films, subtitles are nearly always preferable. This is a special case though, a new creation rather than a straight translation, and a rare brilliant example of creative use of dubbing. The material itself is so odd that the dubbing enhances the seductive dreamlike (nightmare-like?) atmosphere. The violence is wonderfully disjointed and expressionistic, not uncommon in Asian films of this period, but this is perhaps the best I’ve ever seen it done. Chinese film Come Drink With Me does rival in it in terms of wonderfully bizarre and creative violence, but the narrative here is even worse, clumsy to the point of incomprehension. I didn’t know what was going on, and I didn’t really care. Early on, the lead character (apparently) tries to rescue her brother by pretending to be a man but it took a while to figure out that this was what was supposed to be happening – she’s so obviously a woman that the whole concept feels ridiculous. I suppose it doesn’t help that traditional Chinese male dress looks more like female attire to westerners, things are getting lost in translation here. None of this ruins the film entirely, but I can’t help feeling that with a better plot it could have been a masterpiece. The pleasure of Come Drink With Me is the fighting. The beautiful, abstract fighting. It is far from realistic, but something much better: it is cinematic. It is poetic. The elliptical distortions of time and space, the subtly surreal atmosphere astonishes. But as a whole, Shogun Assassin is the better film by far, kept alive by its tender heart, the father/son relationship. The little boy is sublime and his voiceover is used brilliantly (he’s incredibly cute when counting the foes slain by his father). It’s also a handsome film and although it’s not as gorgeous as some of its Chinese peers with their wonderful colours, it does make great use of light and shadow, like the slitted hats the Masters of Death wear. My only criticism is the weak ending, which renders the plot somewhat confusing. Something was likely lost in reworking it, stitching two films into one. No matter. Shogun Assassin has bounties of tactile pleasures to indulge in. I can’t wait for Criterion’s Boxset to discover the whole series of originals.

I saw Come Drink With Me on Film4 as part of their Martial Arts Gold program. This also included Five Fingers of Death, AKA King Boxer. As with Shogun Assassin this is a favourite of Tarantino, and again, it’s obvious, but to Tarantino’s credit he steals from the best. From King Boxer he’s lifted several moments and techniques verbatim for Kill Bill, including the eye-plucking and a memorable sound cue. Whereas Shogun Assassin is luridly brilliant from the start, King Boxer takes a while to get going, but once it does it’s exhilarating. It starts out as your typical martial arts film, slightly bizarre, with some solid yet surreal violence and a much more coherent plot than most in Film4’s Martial Arts season. It’s a little tame, a little dull, but gradually builds up steam to culminate in an ecstatic, lurid and brilliant final act. Words can’t really explain why it’s brilliant. At least mine can’t. So you’ll just have to watch it.

A quick aside: another unexpected favourite of mine last year was Breathless – not Godard’s new wave classic but the trashy American remake with Richard Gere, AKA A bout de souffle Made in USA. I wish I had made notes about it at the time so that I had more to say, but I can say that I enjoyed it hugely and that it’s another big influence on Tarantino. The scenes between Butch and Fabienne in Pulp Fiction are almost ripped directly from this film, but more than that there’s a general pop-culture-infused tone of irreverence that has shaped Tarantino’s work more than anything else I’ve seen. It’s hugely underrated in my opinion, in fact, Tarantino is the only person I’ve ever heard recommending it. It’s currently on UK Netflix, so find out for yourself.

Back to the main subject. Those Asian films from the 60s and 70s may be gory, but by the late 80s films like Tetsuo: The Iron Man took things to new extremes. Tetsuo is completely mad but surprisingly engaging considering how disconnected its narrative is, that is if you could describe it as having one. I admit my interest began to wane towards the end but there’s so much stunning surreal imagery to be able to enthusiastically recommend it. It’s what you might get if you crossed Akira with Cronenberg’s body horror, Sam Raimi’s energetic technique and Jan Svankmajer’s surreal stop-motion creations, and it’s as good as that sounds. My main criticism is simply that the lack of coherence did begin to fatigue me. A longer film might not have worked as well, but at just over an hour long, director Shinya Tsukamoto could afford to be as madly experimental as this, with extraordinary results. With Tetsuo II: Body Hammer, the filmmakers are smart in making a more narrative film whilst keeping the surrealism front and centre. Where the first film is a black and white steampunk horror poem, the sequel takes the somewhat more traditional structure of the 80s action movie, but still appropriates much of the imagery, ideas and abstract techniques of the original. It makes for a vastly different film, but again, brutal and satisfying. They had gone as far as they could with the material in its original form, so this reimagining makes for a great sequel. Aside from the narrative, what’s most striking is the vibrant colour cinematography, opening up new directions visually – and these films are above all else visual experiences.

Speaking of 80s action movies, I want to take a moment to talk about Commando. Silly American Arnie action movie Commando. I can’t believe I’d never seen Commando. Defying all my expectations of tone-deaf over-serious Hollywood dumbness, this is in fact a piece of brilliant camp action comedy from the start, beginning with a ridiculous montage of Arnie and his daughter living in perfect bliss (he playfully gets an ice cream in the face, obviously.) Of course, this bliss doesn’t last long and he finds himself in a race against time to save his daughter’s life. I don’t think I’d be exaggerating to call this one of the best comedies I’ve ever seen, though it’s difficult to tell how much of this the filmmakers intended. Some, certainly. I posed this question to a friend. He said “They must know. They’re adults.” It’s a very fine line, but then it’s a very difficult thing to make a good-bad film on purpose – you cannot be seen to be trying too hard – so this confusion is probably key to its success. On occasion the knowingness is clearer, such as the running commentary of a ridiculous (but nonetheless punchy and effective) fight scene: “These guys eat too much red meat!” Whatever the intention, I enjoyed this film immensely. There are rarely great western equivalents to the transcendently bizarre martial arts films of the east, and this still lacks the grace and poetry in the violence for that, but it’s one of the closest I’ve seen. With added bad puns.